Earlier this week, we published an article on the circular economy and possible shortcomings. The European Union, as well as other economies stress the importance of recycling as an alternative to primary production of key raw material inputs for the lithium battery sector.

Focusing on the EU in particular, if the EU Commission’s new Battery Directive gets drafted into law by 2024, the emphasis on recycled materials as a proportion of the overall materials will have to increase. The stated aim is for around half the weight of lithium-ion batteries (LiB) to be recycled.

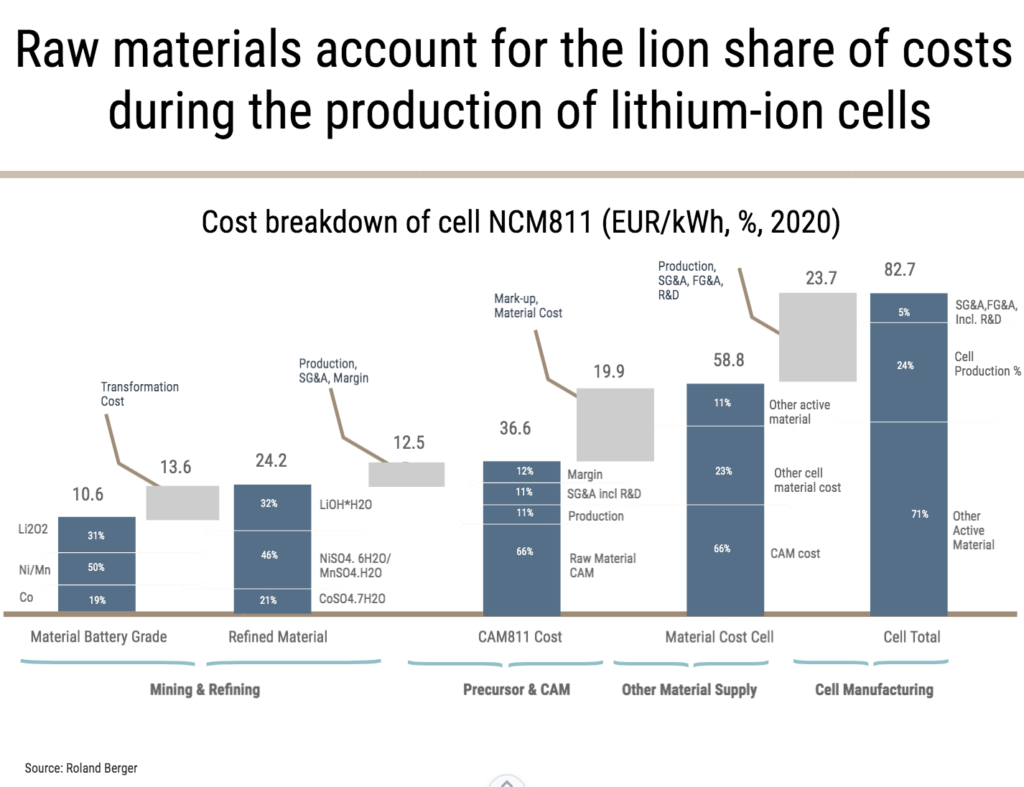

Roland Berger examined the costs of producing a NCM811 battery cathode which they estimate as being EUR82.7/kWh. Of this, the cell material cost accounts for more than 70%.

The EU has enough capacity to undertake polymetallurgical recycling. This is where nickel and copper are recovered through smelting. However, this process has limitations as lithium and manganese cannot be recovered economically.

There is the option to use hydrometallurgical recycling methods where metals are dissolved in solution via leaching and then recovered. This method provides a closed loop recycling system and is showing high potential recovery rates. However, many projects using this method are still in pilot phase.

However, if one is able to recycle these battery raw materials efficiently, the benefits go beyond merely ensuring sufficient supply. Recycling can also be a hedge against fluctuating raw material prices, helping battery makers control costs and margins.

In order to realise the full benefits of recycling and meet the target that the EC has set, there needs to be a clear political framework with which to work. This would need to promote research that is targeted towards the industrialisation of the recycling process. This includes efficient collection and dismantling processes. Furthermore, there needs to be careful considerations as to which metals are recyclable and worth recycling and then to ensure that there are clear incentives to making use of those materials in their recycled form rather than purchasing primary metal. Similarly there may need to be some leniency and dialogue as to the best way to procure materials that are not worth recycling or cannot be recovered and decide on whether to stockpile or to vertically integrate these gigafactories upstream.

Asia is well ahead in this game with extensive support from the state and access to both the primary and recycled materials. At the beginning of November last year, the Chinese Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) spelled out two types of recycling facilities that the industry has to set up that include small recycling centers of around 5 tons of batteries and larger facilities with capacity of around 30 tons. Plant operators are already using digital technologies to track, trace, collect and share inventory data with producers who can then make a decision as to whether the primary metal is needed, or whether stocks of secondary material is sufficient. The deadline for full compliance for the industry was set for May 2020.

With four gigafactories underway in Europe, the region can certainly remain competitive in the cathode space, but the task now is to build up sufficient recycling capacity and a strong legislative framework to support that before Asia gets too far ahead.